The Equal Rights Amendment

By Claire Scripter

A story in documents from Midge Costanza's papers

The Equal Rights Amendment was originally introduced in 1923 by its author, Alice Paul. The amendment read: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and in every place subject to its jurisdiction. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” The amendment went to the states, and by 1977, thirty five of the required thirty eight states had ratified the ERA. As assistant to the President, Midge was working in the White House to assure the ratification of the ERA, in order to guarantee constitutional equality between the sexes, which did not, and still does not, exist. As the original deadline was approaching, Midge and other ERA proponents worked to keep the issue of the ERA on the agenda of the President and the rest of American citizens, including working on an extension for the original ratification deadline. A July 9, 1978 rally was organized, followed by a day of lobbying Congress on July 10, where Midge played the vital role of getting White House support and attendance, in order to assure the American people that the ERA was an important issue in the Carter administration. Although extension was won, and the original deadline was extended from 1979 until 1982, no state ratified the ERA after 1977, and the Amendment died in 1982. The ERA did not pass partly due to its well organized and well financed opponents, including Phyllis Schlafly and her organization Stop ERA, who utilized scare tactics in order to appeal to the emotions of voters and propose ridiculous outcomes that would not have resulted if the ERA had passed. Activists like Midge worked hard in order to ensure the passage of the ERA because they believed strongly in equality for women, despite not knowing exactly how the ERA would be interpreted. However, although its direct effects would be interpreted by courts, “its indirect effects on both juges and legislators would probably have led in the long run to interpretations of existing laws and enactment of new laws that would have benefited women” (Mansbridge, 1986, 2). Passage of the ERA would have been a public commitment to equity for women, and although it did not pass, it did secure success in the form of extension.

The original documents in the Midge Contanza Institute surrounding the ERA have been divided into the categories of extension, the July 9th rally, strategy meetings, unratified states, anti-ERA, and Dear Abby documents.

Extension

While in office, Midge worked tirelessly to extend the ratification period for the ERA. Midge and other feminists fighting for the ERA faced two battles. One to extend the deadline to give states more time to ratify the amendment, and the other to ensure the constitutionality of giving Congress the power to extend the ratification period.

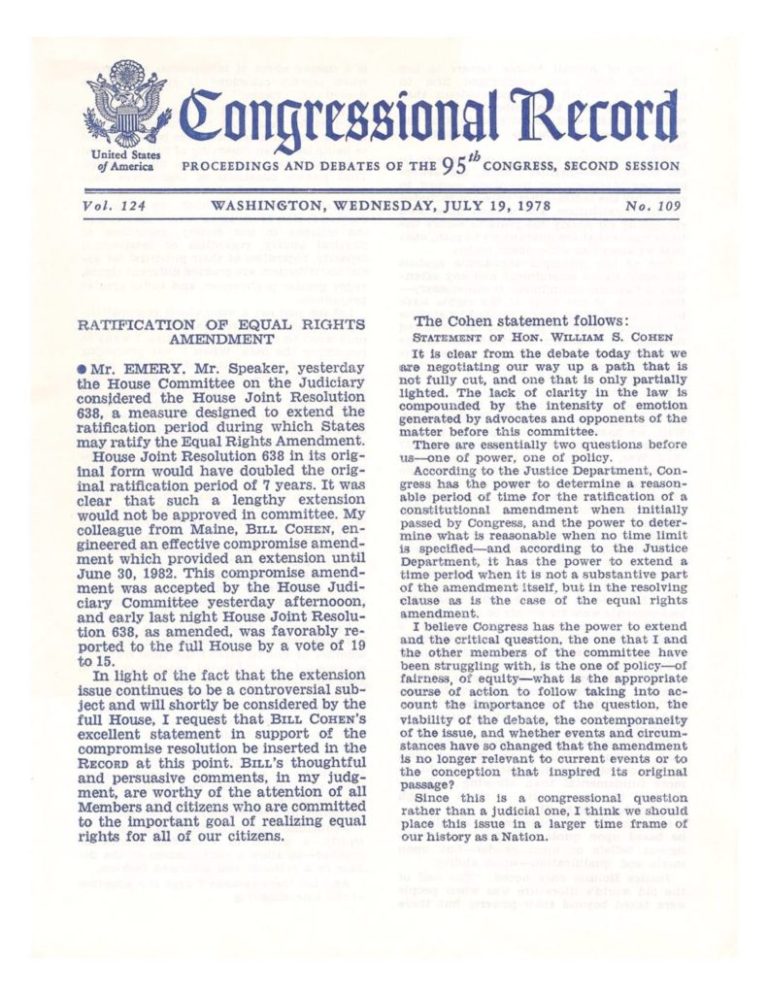

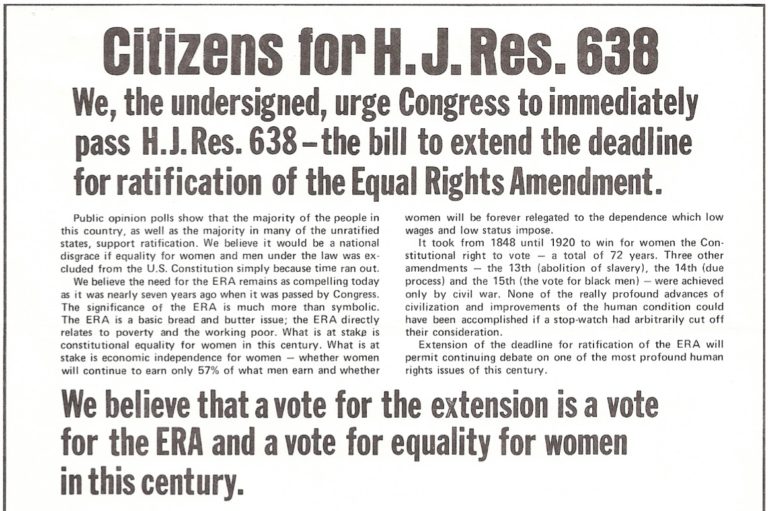

The fight to pass House Joint Resolution 638, the extension resolution, played out in the press (see Documents below). The ERA was still three states short of the 38 state requirement for ratification in 1978, and it was set to expire in March 1979. HR 638 in its original form would have extended the deadline until 1969. However, when it was clear that the 7-year deadline would not make it out of the House, Bill Cohen wrote a compromise to the amendment that proposed a deadline of June 30, 1982. On August 15, 1978, the house debated Resolution 638, lead by Representative Holtzman. As the Congressional Record shows, the compromise amendment passed through the House.

The President advocated for the extension of the ERA, including sending a memo to committee members Peter Rodino and Don Edwards urging them to vote to extend the ratification deadline for the ERA. Midge urged President Carter to show his support for the amendment, reminding him of voting dates, and keeping the passage of ERA on the President’s agenda.

As the ERA had both ardent support and opposition, there was a second battle being fought over whether or not Congress had the power to extend the time period for ratification. However, as outlined in a memo regarding the constitutionality of the extension, based on Article V, Supreme Court decisions, and Congressional precedents, all that was needed was a simple majority vote of Congress to extend the ratification period. The debate surrounding the constitutionality of the extension also included the fact that if states were to be given more time to pass the ERA, they should also be given an opportunity to rescind their ratification. As laid out in the legal memo issued by NOW, according to Article V, rescission is not recognized in that once an act of ratification is carried out, the authority of Article V is exhausted.

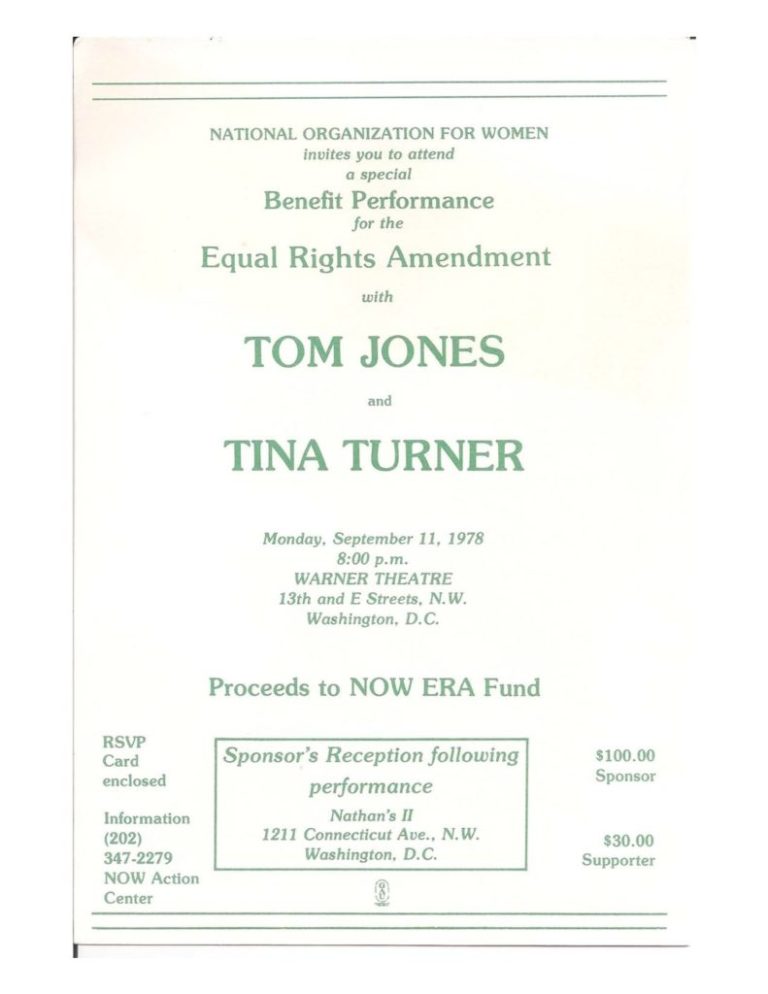

During Midge’s fight for an extension of the ratification period, she was supported by many who wanted to allow for more time for a constitutional guarantee of equity. Although Midge left the White House in August, 1978, support for the ERA continued. On September 11, 1978, a benefit concert featuring Tom Jones and Tina Turner was put on by the National Organization for Women. Midge urged her fellow members of the national commission on the observance of International Women’s Year to attend, or purchase a ticket to support the ERA. Midge was also offered support from former suffragettes, when she was offered an original banner worn during suffrage parades to aid in her efforts to pass ERA.

After the extension passed, Midge acknowledged her success in giving the ERA a continued chance, but did not stop fighting to guarantee equality for women under the law. In a letter to Ellie Smeal, she thanked the president of NOW for her support, and acknowledged a victory. Later that same month, in a memo to the White House senior staff, she urged her colleagues to keep her informed of any ERA related activities taking place, as the fight was not over.

Documents and Articles

Rally

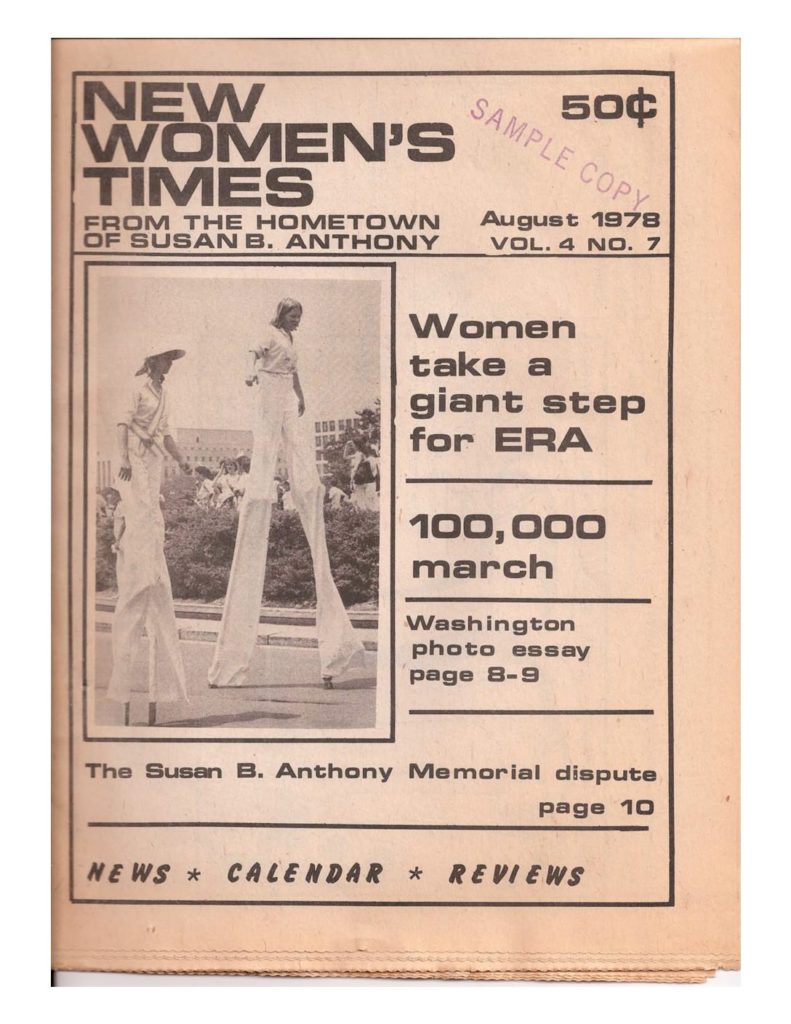

On July 9, 1978, the National Organization for Women (NOW) organized a rally to demonstrate grassroots support for the ERA and extension. It was followed by a day of lobbying Congress on July 10. Midge played a vital role in the success of the rally by working to garner White House support and attendance. She sent out memos to many in the White House urging attendance. In particular, she sent first lady Rosalynn Carter an invitation to speak at the rally. Although Rosalynn Carter was a supporter of the ERA and extension, she declined the invitation because the Carters were at Camp David that weekend.

The rally was an attempt to recreate former suffrage parades. July 9th was a significant date in that it was the one year anniversary of Alice Paul’s death. Paul authored the ERA, and organized the first suffrage parade in Washington D.C. on March 3, 1913. The July 9th rally organizers urged participants to wear white, as the suffragists had. Over 365 organizations were in attendance, including Feminists of Faith, a group representing all religious women for the ERA. Planning for the rally was detailed, and NOW prepared a fact sheet because so many visitors were expected in Washington. NOW investigated low cost housing, and even searched for shelter that could hold sleeping bags. Participants in the rally were encouraged to spend the night and to participate in the ERA lobbying day on July 10th.

Midge spoke at the rally, delivering a statement (see Documents below) by President Carter, who did not attend. The statement was in support of the ERA, outlining the ERA as a human right, and assuring women that there was no time limit on the Carter administration’s commitment to equal rights and equal opportunity. According to a Washington Post article about the rally, when Midge addressed the crowd and told them she had a message from the President, she was met with both applause and boos, as well as shouts of “Where is he?” Some felt that if the President cared so much about the ERA, he should be in attendance at the rally in solidarity with the women fighting for Constitutional equality.

According to the press (see Documents below), the turnout for the rally was between 65,000 and 100,000, which made it the largest rally for women’s rights in the nation’s history at the time. The turnout was much more than the expected 20,000 to 30,000 people, and it was even more remarkable considering the hot, humid weather. Women came from across the country to hear the speech not only from Midge, but also actress Marlo Thomas, actor Elliott Gould, EEOC Chair Eleanor Holmes Norton, activist Gloria Steinem, activist Bella Abzug, activist Betty Friedan, and Representative Elizabeth Holtzman. No anti-ERA activists organized opposition to the march, although, Phyllis Schlafly called for a nationwide day of prayer on July 9.

There was also negative press surrounding the rally, including one Washington Post article that stated “marching for the ERA in the summer of 1978 is approximately as inspirational as taking part in an American Legion parade.” The journalist was critical of the amount of time it was taking for the ERA to pass, and held the opinion that whether or not citizens were for the ERA, they were tired of hearing about it. One cartoonist took a jab at the decision to march on a summer day when legislators were unlikely to be at work, showing his ignorance to the significance of July 9 as the anniversary of Alice Paul’s death. Some negative coverage opposed the idea of extension in general, advocating for the original seven year period as “a wise and realistic method to protect the Constitution from amendment by endurance.”

The press also articulated the mood after the rally as a somber one, not because of anti-ERA sentiments, but as a result of being discouraged by a government that did not value human rights. While women were excited at the rally, mobilizing for a cause they believed in, upon reflection, they worried about the impact it would have. According to Ronnie Smith, who worked in the state division on human rights, “I’m so discouraged in general about what’s happening in my field.” However, these women did not show signs of backing down, as one woman at the rally stated, “if it doesn’t pass, I-I’ll become more militant, that’s what.”

Documents and Articles

Strategy Meetings

While in the White House and advocating for the passage of the ERA, Midge held various strategy meetings in an attempt to keep the ERA on the President’s agenda and tackle issues surrounding the vote for the extension period

On Monday January 30, 1978, Midge met with Ellie Smeal and Arlie Scott of NOW to discuss the ratification of ERA and a possible extension for ratification. In the meeting they discussed a trip to South Carolina, NOW strategy, and possibilities for the celebration of Susan B. Anthony’s birthday.

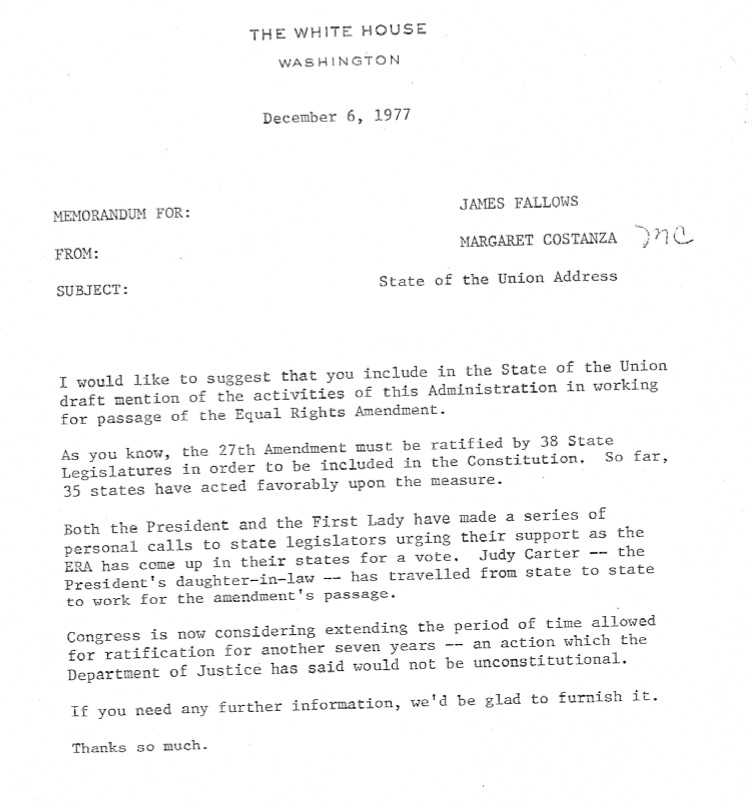

Midge worked in the White House to keep the ERA on the agenda of the President and other members of Congress. In this memo to James Fallows, President Carter’s chief speech writer, Midge suggests that the work being done towards the passage of the ERA be included in the President’s State of the Union Address. In the memo, she urges support for extension, and reassures Fallows that the department of justice has said extension would not be unconstitutional.

On Monday, February 13, 1978, (see Documents below) Midge met with Arlie Scott of NOW, Mildred Jeffreys of the Women’s Political Caucus, Irma Finn Brosseau of Business and Professional Women, Nancy Neumann of the League of Women Voters, and Kathleen Currie of ERAmerica to discuss the ERA. The meeting took place in Midge’s office, and the women discussed state ratification failures, a possible economic boycott, and a possible Presidential statement.

Midge and other women in the White House put pressure on President Carter to keep the ERA on his agenda. While Carter publicly supported the ERA, he did little himself to assure its passage and the passage of the extension. In a March 2, 1978 letter, four female members of Congress are demanding a presidential strategy for the passage of the ERA, reminding President Carter that he had tools, resources, and techniques at his disposal for jawboning and moral persuasion. By keeping the President accountable for his actions, Midge and women in Congress fighting for Constitutional equality were reminding him that women were not going to sit back and wait for equal rights to come to them according to what was convenient for the President.

Documents

Unratified States

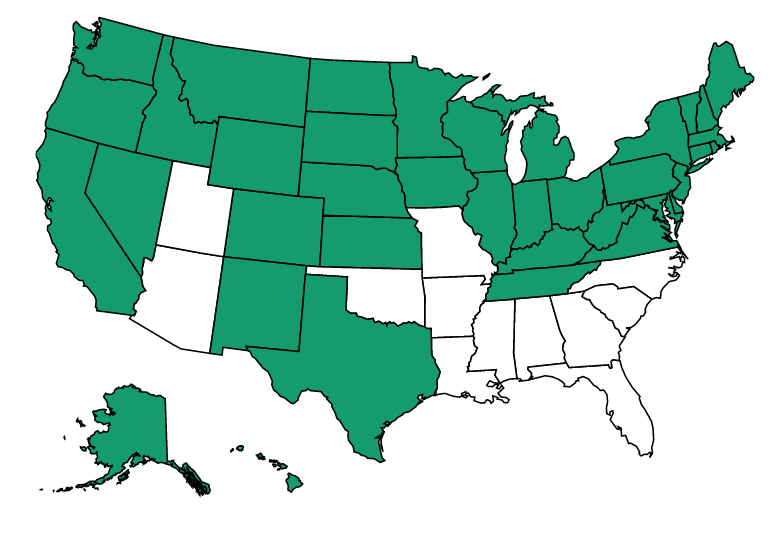

As of 1978, the ERA was still three states short of the 38 state requirement for ratification. The status of the fifteen states that had not yet ratified the ERA differed. Midge and other ERA activists focused their strategies on Florida, Illinois, and North Carolina, in an attempt to convince voters of the importance of ratification.

In Florida, the Senate vote roll call played a part in Midge’s strategy. On April 11, 1977, Midge sent a memo to President Carter, urging him to make a call to democratic senator William G. Zinkil. Zinkil was last on the roll call for the senate vote, so his affirmative vote would be heard throughout the nation as a commitment for ERA ratification, and a commitment to equality in general. Midge called Zinkil herself, but he assured her that once he had made up his mind, the only person he would discuss it with was the President.

In strategy surrounding Illinois, ERAmerica created a detailed list of what the President should do when he visited the state in May, 1978. ERAmerica sent their proposal to Midge, who forwarded their message to the President through a memo dated May 20, 1978. The proposal included a suggestion that President Carter include the ERA in his speech before the General Assembly, and reminded him that the votes necessary for ratification would be present at the Cook County Democratic Dinner that he was attending as a part of his visit to Illinois. Midge also outlined her support for the Committee for the ERA in Illinois in a letter dated April 26, 1978.

In North Carolina, the First Lady played a role in strategy planning. In a memo to Mary Hoyt, press secretary to Mrs. Carter, Barbara Dixon of Senator Bayh’s staff asked that the First Lady place phone calls to Democratic legislators in North Carolina.

Anti Era

If the ERA had passed, it would have guaranteed equity between men and women under the Constitution. The majority of those who opposed the ERA did not necessarily oppose equality, but opposed specific potential changes that might have occurred as a result of the amendment. For example, a poll conducted by the Committee on the Status of Women in 1977 reported American people opposed sending women into military combat, giving the Federal Government power in cases of marriage, divorce, and child custody, and making school activities coed. Anti ERA activists utilized scare tactics in an attempt to advertise outrageous potential outcomes of passage of the amendment and mobilize opponents against the amendment. By scaring voters into thinking their daughters would be on the front lines as a result of the ERA, or that proponents of ERA were anti-family or anti-men, opponents of the ERA were able to scare citizens into making a decision about the ERA without considering what it would actually do. Although it was unclear what actual implementation would look like, some press argued that equality for the sexes could result in high costs for society in general. Supporters argued that the ERA would not have guaranteed any of these changes but the most important way the ERA would have helped women was as a public statement of moral commitment to equality between the sexes. (Mansbridge, 1986, 42).

One issue the opposition mobilized around was the effect the ERA would have on the draft. Operation Wake-up was an anti-ERA organization that distributed documents (see Documents below) regarding women and the draft, seeking to convince voters that the passage of the ERA would lead to women on the front lines. By arguing that as a result of the passage of the ERA, women would be forced into the draft and onto the front lines, the opposition utilized scare tactics in order to make an emotional appeal to voters. In reality, Congress already had the power to draft women if they needed to, and if the ERA had passed, it would have been up to the Supreme Court to decide if the military would become blind to sex. However, by arguing that if the ERA passed, Congress would be forced to draft women whenever they had to draft men, Operation Wake-up sought to convince voters otherwise. Ultimately, Congress could not be forced to draft female soldiers regardless of whether or not the ERA had passed, as the “war powers” clauses of the Constitution allow the military to be exempt from even the Bill of Rights.

A second issue anti-ERA groups mobilized around was Social Security as it related to homemakers. As homemakers do not earn wages, they are not paying into Social Security, and benefits available to nonworking spouses are less comprehensive than those available to workers who paid into the system (Mansbridge, 1986, 53). As a result, the present Social Security system “does not value a wife’s contribution to a marriage as highly as her husband’s, if the wife is a homemaker” (Mansbridge, 1986, 53) and opponents argued that implementation of the ERA could require husbands to pay social security on the assumed earnings of their wives. The opposition saw this as an attack on homemakers, as families would no longer be able provide for their families with one income. Annette Stern, founder of Operation Wake-Up, wrote about what she believed the ERA would do to social security, and to homemakers. However, supporters argued the ERA would have protected homemakers in the event of divorce by recognizing their unpaid work as sacrificing a paid career. States with ERAs in place have proven that when women are protected under state constitutions, judges are more likely to give them more property in divorce settlements after calculating forgone earnings (Mansbridge, 1986, 94).

In addition to opposing specific changes that might have occurred if the ERA passed, anti-ERA groups also opposed the ERA as a blanket approach to equality, and favored specific legislation that would protect women. Barbara B. Smith, president of The Relief Society of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, argued (see Documents below) that women should have equal rights, and have always been given equal rights, but it is better to protect them through individual legislation. Many including Barbara Braun of Women for Women’s Rights, and Women United to Defend Existing Rights also opposed the ERA on the grounds that it would give too much power to the federal government because the Supreme Court could interpret the ERA as it saw fit. Anti-ERA groups appealed to the public by advocating for an end to unfairness through specific legislation, while still opposing Constitutional equality between the sexes.

The face of ERA opposition was Phyllis Schlafly, the founder of Stop ERA and a conservative political activist. Schlafly was active at the same time as Midge, and the two were on opposite sides of the issue of the ERA. Schlafly argued that the ERA would take away the special privileges allowed to women, who belonged at home as mothers taking care of their husband’s children. She made a direct appeal to homemakers, and argued that the ERA would dismantle the traditional nuclear family. Schlafly’s views and politics were in direct contradiction with her activism, as although she advocated for a woman’s role at home as a full-time mother, she was always traveling on speaking tours, and living the life of a political activist. As she was the face of the opposition, she testified against the ERA before the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights, arguing that proponents of the ERA were the organized minority, pressuring the legislative body to vote again and again until the motion passed.

Opposition to the ERA did not just lie in religious groups advocating for the protection of housewives, or groups that were against giving more power to the federal government. In one instance, an article in the Washington Post argued that losing the extension would be beneficial to feminists. The article made the point that the movement needed to reassess its strategies in order to be politically successful. Instead of assuming the ERA is a human right, the movement needed to be politically successful, requiring a translation of the issues at hand. “The movement away from principle and the increasing focus on substantive effects was probably an inevitable result of the ten-year struggle for the ERA” (Mansbridge, 1986, 4) and this article made the point that the feminist movement might benefit from a reassessment that would certainly occur if extension had not passed.

Pro-ERA activists like Midge and the National Organization of Women worked to make sure that those groups and states that opposed the ERA would face consequences. NOW organized a convention boycott on states that had not ratified the ERA. In 1978, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists held its convention in an ERA ratified state, and overall NOW estimated that the revenue loss for the 15 states not ratified amounted to over $100 million.

When the original seven year extension period expired, Phyllis Schlafly and her supporters were quick to celebrate. They claimed the ERA was dead, morally and constitutionally, and celebrated (see Documents below) with a gala at the Shoreham hotel with over 1,000 guests. Schlafly claimed the expiration of the ERA was the greatest victory for women’s rights since the passage of the suffrage amendment.

Documents and Articles

Dear Abby

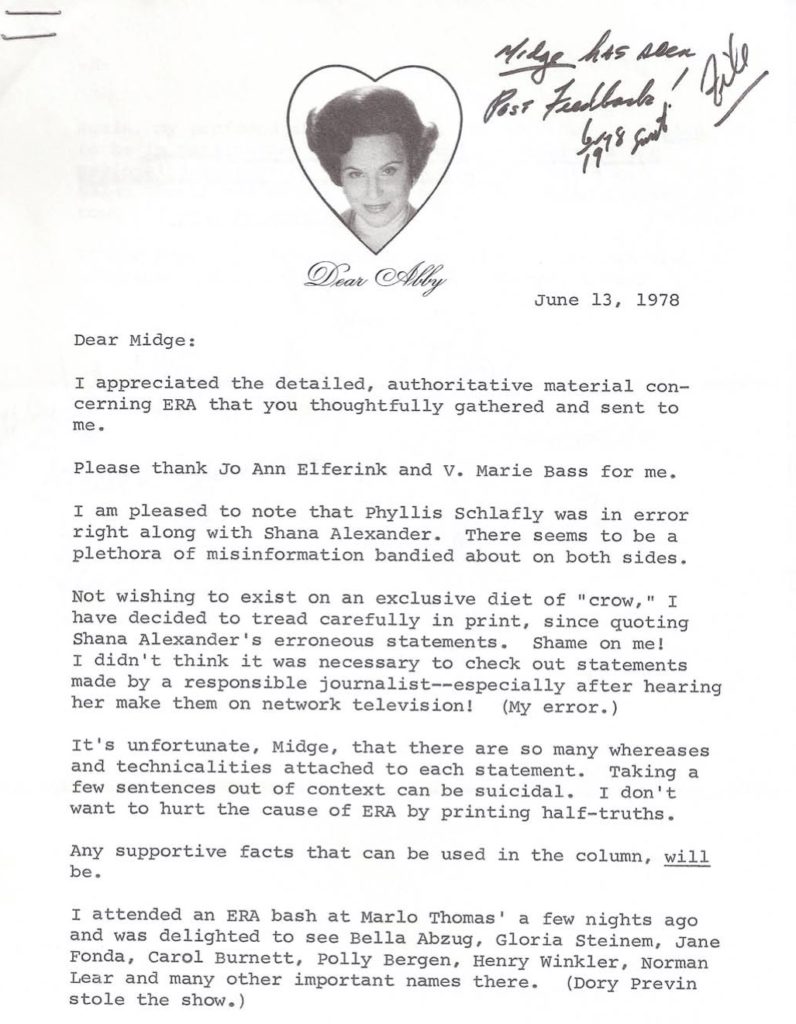

Midge’s commitment to the ERA and her commitment to ensuring the population had access to the facts about the ERA and not just scare tactics can be seen through the development of her relationships with Dear Abby. On April 24, 1978, the Washington Star published its Dear Abby section, where a reader wrote in confused about why Abby supported the ERA. Abby answered by quoting journalist Shana Alexander’s debate with columnist James J. Kilpatrick on “60 Minutes”. In response to the column, Senator Joan Gubbins wrote a letter to Abby, questioning her support of the ERA and critiquing the facts Abby put forth, asking her to tell the truth instead of fantasies. Phyllis Schlafly also responded to Abby’s column with a letter calling Shana Alexander’s charges “so false they are ridiculous.” In addition to the letters from Schlafly and Gubbins, Abby received a letter from a Florida law firm warning her that her column “misquotes the law incorrectly in every aspect.”

In response to the upheaval surrounding her column, Abby wanted answers about what the ERA would really do, and so she contacted Midge’s assistant, Joan Elferink, and attached the letter from Schlafly, asking Joan and Midge to respond to the letter point by point so she would be able to respond with intelligence and authority. Elferink sought answers herself, so she inquired with ERAmerica, and received a response in the form of a letter from Marie Bass, Campaign Director of ERAmerica, with a memo responding to each point Schlafly raised in her letter to Abby.

Midge eventually responded to Abby with a comprehensive packet of information surrounding the issue of the ERA, including a letter to Abby outlining the information she had obtained. The information Midge sent Abby included a memo dated June 5, 1978, that detailed the errors in both Schlafly’s and Alexander’s letters, and addressed the specific issues raised by the women, including Social Security, divorce, pregnancy and disability, and inheritance tax.

In conclusion, Abby sent a letter to Midge, thanking her for her detailed material concerning the ERA, and taking the blame for “quoting Shana Alexander’s erroneous statements” in the first place.

Mansbridge, Jane J. Why We Lost the ERA. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986. Print.